Hello and welcome to Translator’s 20th Dispatch!

From Dispatch #1 to now, it’s been such a pleasure sharing with you our summaries of stories from around the world that have fascinated, engrossed, delighted and sometimes horrified us.

It’s already been such a journey, one that has taken us – and you – into the richness and diversity of global journalism and writing: from an analysis of the political situation in Turkey to articles about Italian 1980s telemarketing and indigenous radio stations in Guatemala; from how Trump’s tariff war is being reported in Vietnam and Egypt to powerful stories from the lives of women from Iran, Iceland and Indonesia.

We believe that there are urgent, necessary stories all around the world. Our goal is to help you read the world differently. Translator’s weekly Dispatches are our way of starting that off.

Thank you for reading our summaries of articles from beyond the Anglosphere each week. We’ll keep on doing that going forward. Tell your friends and colleagues. Recommend stories you think we should summarise or translate from languages other than English.

Translator is for you, whether you speak one language or five.

Translator Issue #1

This week, we have some particularly exciting news which goes a lot further.

Over the last months, we’ve been working with publications, translators, and writers from all around the world to give you something completely new: our first print magazine, coming out on 26 June.

It’s available for pre-order here.

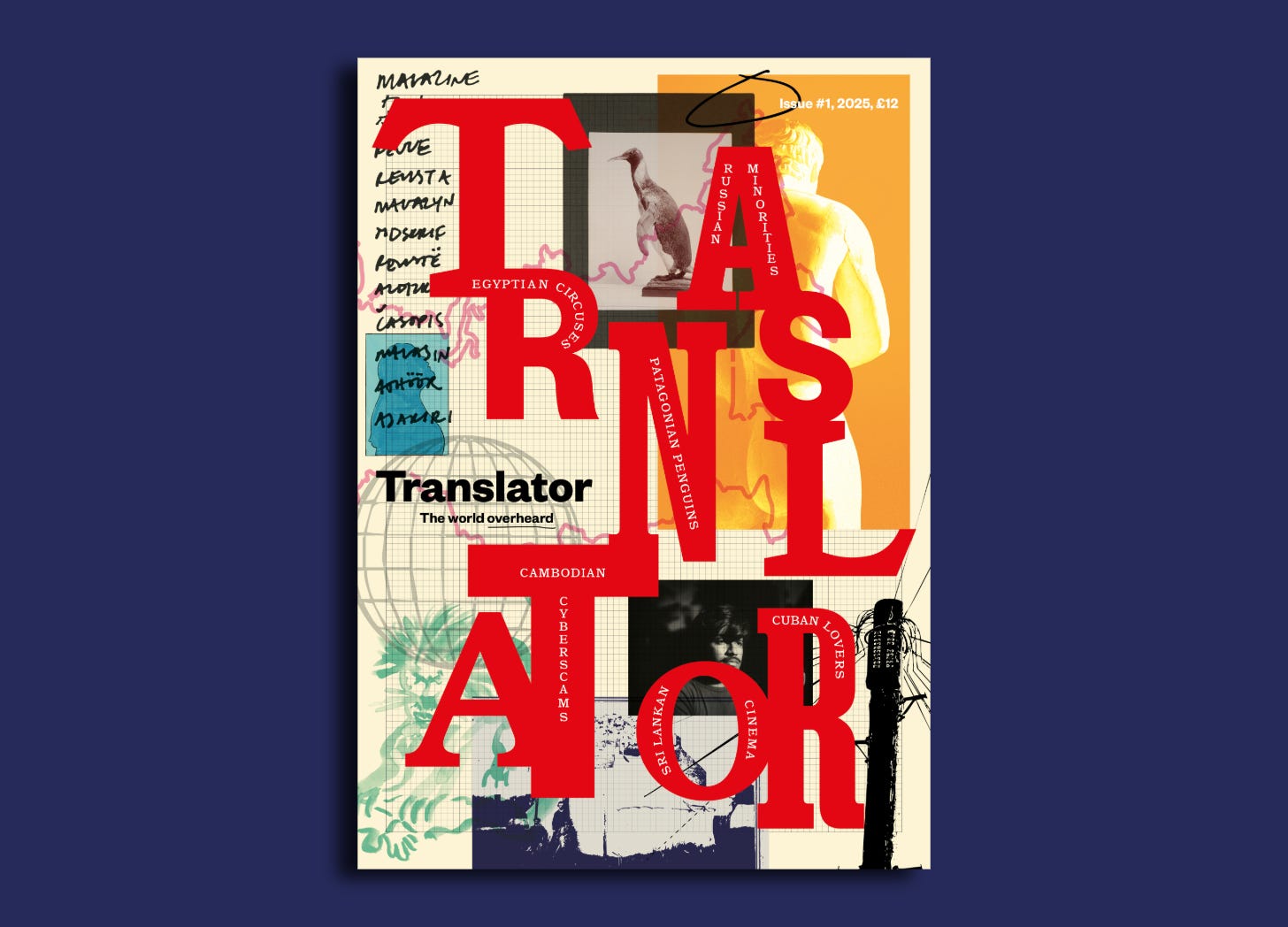

Here’s the wonderful cover, designed by the team at magCulture:

The magazine is a mix of full-length articles from the best media outlets beyond the Anglosphere, professionally and lovingly translated into English; articles about the role of language in our world; and shorter commissioned pieces giving you the word on the street in cities from Medellín to N’Djamena.

For each translated article, we’ve commissioned a different illustrator from beyond the Anglosphere.

Over the next couple of weeks, we’ll be revealing more of the contents of the magazine here and on social media, giving you early access to events and other Translator goodies, and ways to support what we are doing (and getting something in return). Follow us on Instagram and LinkedIn to find out more.

You’ll be able to get your hands on a copy of the magazine from the end of this month in selected shops. You can already pre-order it online.

In the meantime, we wanted to share the beginning of just one of the pieces of translated reportage we love from the magazine, the opening of a fantastic, mesmerising story by Verónica Bonacchi for the excellent independent Latin American publication Gatopardo, translated by Ali Sargent, a writer and translator from Spanish and Portuguese based in Mexico City.

‘The Massacre of the Penguins’ is an extraordinary piece: part true crime investigation, part meditation on our relationship to nature, part family saga, part introduction to the fascinating history of this southernmost part of Latin America. The rhythm of the story reflects the landscape where it takes place: spare, beautiful, surprising. Reading it, one can hear the wind of the place, one can feel the sense of being on the edge.

But at the heart of the article are questions which burn across the world: the boundaries we draw – between each other, and with nature – and how to get justice when those boundaries are crossed.

The original Spanish version is available here.

We hope you enjoy this excerpt.

The Massacre of the Penguins

Original in Spanish by Veronica Bonacchi, Gatopardo; translated by Ali Sargent

It’s hard to find the right words to describe the extraordinariness that occurs each year in Patagonia, on Argentina’s Atlantic coast. Hyperbole could only begin to capture what happened there in 2021: events that have come to be known as the massacre of the penguins.

It must have been the same back then as it is now, nearly a hundred years since the first Magellanic penguin made landfall on this beach in the Patagonian province of Chubut, the endpoint of a 3,200-kilometre swim from Brazil.

A penguin, the same as now: agile and athletic in the sea, fast underwater; but with a clumsy, swaying, short-stepped gait on land. He shakes off the last of the saltwater and smartens up his black and white feathers. The penguin walks inland, unsteadily, chest puffed out, until he finds a patch of soft, dry earth under the branches of a Quilimbay or Jume tree. Just as they do today, he uses his beak to dig a sloping burrow, 70 centimetres into the ground. He shooes away the dust with his wing and begins to wait, sheltering until the arrival of a female a few days later.

This is how it must have happened – penguins, after all, are creatures of habit.

2024: The slow trickle of penguins gathering in Punta Tombo, a 210-hectare (2 square kilometre) protected area on the Atlantic coast, cock their heads and throw a sideways glance in the direction of the tourists and the contingents of school children whose arrival marks the beginning of the season. It’s 11.30 in the morning on September 16. The sun is mild. The wind is exceptionally light. The penguins pay no heed to the politicians who have shown up to cut ribbons and give speeches. They ignore the mobile phones and cameras turned towards them. They take their time to cross over the kilometre and a half long wooden walkway which intrudes into their habitat, built so that the visitors can gawk at them up close while keeping the 2-metre distance the warning signs require; these penguins, such an emotive symbol of relational fidelity and responsible co-parenting – the males and females raise their young together – thanks to the Oscar-winning 2006 French documentary, March of the Penguins.

It must have been imperceptible at first, the gradual expansion of the area occupied by the penguins each September-to-April mating season, starting in 1929 and eventually growing to some 400 hectares (4 square kilometres). Back then, this land wasn’t yet a province, still less a nature reserve, home to the half million penguins that today make it the continent’s largest penguin colony. The Magellanic penguins were not yet at the mercy of family feuds, personal ambitions or the courts. They weren’t yet subject to a tourism industry that sells them in the form of stuffed toys and depicts them on the side of taxis, on alfajores and on posters, t-shirts and other souvenirs, and which attracts over 85,000 visitors a year to wander among their nests and their young for a fee of $19 for foreigners or $6 for Argentinians.

It would take 92 years for all that to come together; and then for their habitat to be flattened by a multi-tonne machine and divided up with an electric fence.

The 2021 events that have come to be known as the ‘Massacre of Punta Tombo’ in fact took place some 9 kilometres away in the lesser-known and less frequently visited Punta Clara. The incident led to a court case in which 37-year-old Ricardo La Regina, manager of an area of land which partly overlaps with the penguin colony, was accused of aggravated environmental damage and cruelty to animals. Specifically, La Regina was alleged to have used a mechanical digger to open a 930-metre-long pathway through the colony, crushing eggs and baby penguins as he went, killing 105 birds and destroying 175 nests.

It started on the morning of August 10, 2021. And in this story, dates matter. Ricardo La Regina repeatedly stated that everything he did was over and done with in August; that is, before the arrival of the penguins. Against this, the prosecution – backed up by satellite imagery and expert reports – stated the bulldozer was in fact used multiple times after that first August morning, and up until December 4; that is, at a time when eggs had been laid, penguins were brooding over them, and some chicks had already hatched. The eight months the penguins spend on the coast at Chubut are a key part of their reproductive cycle.

But all this occurred in the middle of an expanse of 10,000 hectares of desolate Patagonian bush, amidst the Quilimbay and Jume trees, buffeted by a constant wind coming off the sea. Until 22 November 2021, none of what happened was seen or heard. Up till then, there was no body of evidence. The crime scene had to be reconstructed…

This excerpt is taken from Translator Issue #1, out on 26 June. To read on, pre-order a copy of the magazine here.

That’s all for now – we hope you’ve enjoyed the read. Keep an eye out for our next Dispatch of summaries this time next week!

The Translator team